While many people mourn the disappearance of Sunday book sections in newspapers across the U.S., the number of quality sites online—The Millions and The Los Angeles Review of Books come to mind— for high-quality book reviews, criticism and literary essays continues to grow. I recently spent time clicking through the excellent site Full Stop, which is finishing its first year online.

The website’s mission is to “focus on young writers, works in translation, and books we feel are being neglected by other outlets while engaging with the significant changes occurring in the publishing industry and the evolution of print media.”

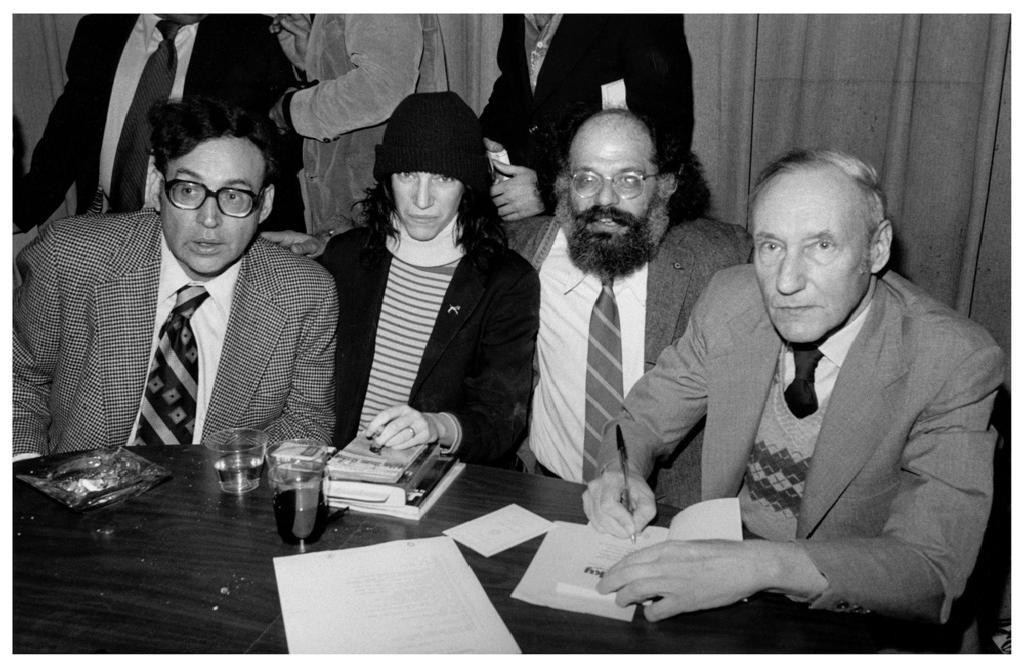

Writer and musician Alina Simone.

Writer and musician Alina Simone.

In visiting Full Stop, I came across a number of intriguing articles, including an interview with musician and writer Alina Simone who had no intention of writing a book until an editor at Farrar, Strauss & Giroux heard her music. The encounter led to her collection of essays You Must Go and Win. She explains:

“…(the editor) really just heard me on Pandora. I don’t really know what he was thinking. Maybe in some way it was based on the lyrics to my songs? I’m guessing that he had some feeling that I could write. I don’t know really what that was based on, exactly. He insists it was just the music – he heard the music and thought I could write a book. You know? I don’t know, maybe editors develop some sixth sense about a person.”

George Saunders is one of several authors that chime in on “The Situation in American Writing.”

George Saunders is one of several authors that chime in on “The Situation in American Writing.”

There is also a series on the website now called “The Situation in American Writing.” It’s based on a 1939 questionnaire The Partisan Review sent to a number of prominent writers. Full Stop updated the questions and writers like George Saunders, Kio Stark and Marilynne Robinson, who wrote the Pulitzer Award-winning novel Giliead, give their two cents. Robinson writes about the current state of literary criticism:

“For a long time the academy has been training people in a style of criticism that is marked by nothing so much as jargon, and by generalization that is pointedly inattentive to the character of any particular book. So there is a great breach between the persons of letters who would otherwise lead the public conversation about books and the vast majority of the reading public. No wonder they are so small a voice. It would no doubt enhance our awareness of the serious writing that does indeed go on if there were critics of the kind that used to introduce such writing to a serious readership.”

And then to the delight of a Japanophile like myself, there was a lengthy essay by Steve Vineberg about the new Criterion DVD release of the 1983 Japanese movie The Makioka Sisters, which is based on the novel by Junichiro Tanizaki.

Vinberg writes beautifully both about Japan and film:

“The movie — one of the most magnificent-looking ever released — is conceived largely in terms of wide, carefully composed long shots that emphasize the formality of traditional Japanese life; of the astonishingly graceful, flowing movement of the four sisters; of the sumptuous silk kimonos they wear, which glide and slither (and are never supposed to squeak), and in one breathtaking scene are hung and layered like screens for the set of a bunraku puppet play; and of the lyricism of the landscape, which Ichikawa and Hasegawa capture in different seasons. (Intriguingly, the music Ichikawa chooses is western: it’s by Handel. But its stately classicism seems ideal for the material.)”

I would say Full Stop is worth adding to your RSS reader.

![By Allenginsberg_cropped.png: *Allenginsberg.jpg: MDCarchives derivative work: Morn (talk) derivative work: Morn (Allenginsberg_cropped.png) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/22/Allenginsberg_cropped.jpg)