I’m still on an Elif Batuman kick. I’ve been tracking down her essays online and I’m looking forward to reading The Possessed, which arrived in the mail yesterday. Batuman wrote a funny, blistering and brilliantly-argued essay in the London Review of Books in 2010 titled “Get a Real Degree” where she reviewed Mark McGurl’s history of MFA creative writing programs.

It isn’t entirely surprising that Batuman, who has a PhD from Stanford and is a Russian literature professor, is no cheerleader for programme fiction. What’s surprising is that Batuman writes with a sense of wit and style that must be the envy of many fiction writers.

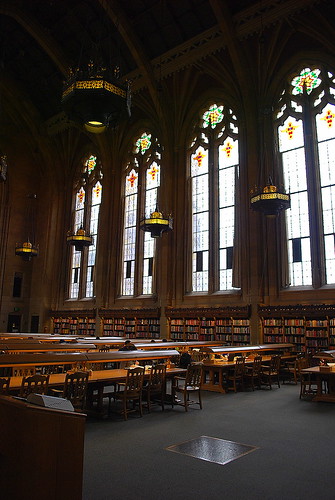

![]() photo credit: JoeInSouthernCA

photo credit: JoeInSouthernCA

The following provides a sense of her flare as a reviewer as well as her skepticism about programme fiction:

“In technical terms, pretty much any MFA graduate leaves Stendhal in the dust. On the other hand, The Red and the Black is a book I actually want to read. This reflects, I believe, the counterintuitive but real disjuncture between good writing and good books.”

It is undeniable that contemporary “literary fiction” is now dominated by graduates of MFA programs; Batuman finds these books largely deficient:

“I think of myself as someone who prefers novels and stories to non-fiction; yet, for human interest, skillful storytelling, humor, and insightful reflection on the historical moment, I find the average episode of This American Life to be 99 per cent more reliable than the average new American work of literary fiction. The juxtaposition of personal narrative with the facts of the world and the facts of literature – the real work of the novel – is taking place today largely in memoirs and essays.”

Her long essay makes a number of interesting points; in no particular order, they are:

- Programme fiction has little “historical consciousness”

- Programme writers are obsessed with writing about persecution & the persecuted (sounds similar to Harold Bloom’s complaint about what he termed the “literature of grievance”)

- She challenges McGurl’s contention that until the advent of the GI Bill in the U.S., writers had generally forgone a university education

- The whole project of literature as a “means to social change” (à la Dave Eggers) is something she remains suspicious of

![By Allenginsberg_cropped.png: *Allenginsberg.jpg: MDCarchives derivative work: Morn (talk) derivative work: Morn (Allenginsberg_cropped.png) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/22/Allenginsberg_cropped.jpg)