Zohra Drif strode into the Milk-Bar in Algiers on a hot September day in 1956. She ordered a milk shake, sat down, and calmly sipped from the straw as she checked and rechecked her wristwatch. The Milk-Bar was the largest ice cream parlor in Algiers, and a favorite stop for French-Algerian families, the pied noirs, who lived in European enclaves under the colonial system of France.

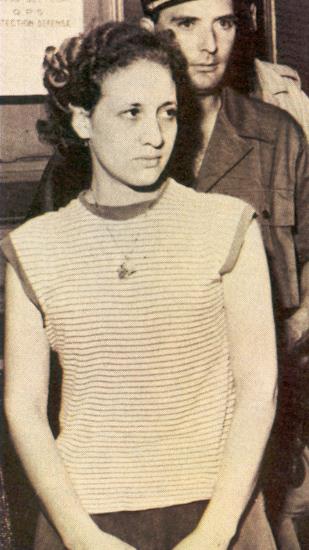

In the Milk-Bar Drif was a “foreign agent” despite being an Arab Algerian. Her country was two years into a war between French authorities and Algerian independence fighters, and as a result, the European quarter was off limits to most Arabs. But Drif, a 21-year-old law student from a prestigious family, had passed through the French checkpoint undetected because she spoke French fluently and sported a European-style summer dress and haircut. The gendarmes could not have known she was a member of the notorious F.L.N., The National Liberation Front, which attacked both military targets and civilians in its war to free Algeria from French rule.

At 6:20pm Drif paid her tab, pushed a beach bag with a bomb under the table, and walked out. The bomb exploded a minute later and just before a second F.L.N. bomb in the Cafétéria, a popular European student hangout across town. The two bombings left three civilians dead and over 50 injured, a number of whom were children.

“The carnage was particularly appalling in the Milk-Bar,” wrote historian Alistair Horne. “Where the heavy glass covering the walls was shattered into lethal splinters.”

The terrorist attacks on September 30, 1956 were born of a string of setbacks that had convinced F.L.N. leaders they were losing the war. F.L.N. commander Youseff Zighout decided the only option was to declare a total war on all European civilians (along with French pied noirs, they were also European residents of Spanish and Italian origin). Zighout wrote: “To colonialism’s policy of collective repression [author’s italics] we must reply with collective reprisals against the Europeans, military and civil, who are all united behind the crimes committed upon our people. For them, no pity, no quarter.”

The French Overreach

Horne writes that Drif experienced a moment of doubt in the Milk-Bar as she looked at the happy mothers and children after a day at the beach. She was crossing a forbidden boundary, but she steadied herself by thinking of French atrocities. “I was a solider in our national liberation army,” Driff told the BBC News in 2022. “We were at war. European civilians were occupying our country.”

Predictably, the attacks provoked an overwhelming, and disproportionately lethal, French military response. Instead of using police agents to target only F.L.N. terrorists for arrest and/or assassination, the French brought in the elite 10th Para Division of the French Army. The Battle of Algiers began, and with it, a wave of repression, torture, and overreach that would doom the French Fourth Republic and the French rule in Algeria.

*

In a 2018 Nation review of Drif’s memoir: Inside the Battle of Algiers: Memoir of a Woman Freedom Fighter, Bill Fletcher Jr. wrote: “The F.L.N. saw their actions as retaliatory violence. But they also saw the settler population as part of the enemy. This conclusion seems neither illogical nor irrational. The overwhelming majority of the pieds-noirs believed in what they called Algérie Française.”

Fletcher’s description is emblematic of the kind of moral confusion we are witnessing in the aftermath of Hamas’ massacre of approximately 1,400, mostly Israeli civilians, in their communities, homes, and cars. You may notice that Fletcher uses a double negative (“neither . . . nor”) to obfuscate what is clearly an affirmation of terrorist logic.

At the risk of stating the obvious, I’ll be quite clear: it is profoundly illogical, not to mention immoral, to deliberately kill civilians because of a conflict with a government and its police, military, judicial, and political system. It’s like cutting down a tree because you hate the rain. It’s a specious argument: no more, no less. There are counter examples of powerless people using non-violent means—the African National Congress in South Africa, The Solidarity Movement in Poland, the civil rights movement in the U.S—to achieve significant political ends.

There have also been armed liberation struggles that justly employed violence against the military targets of an oppressive government or occupying force; Fidel Castro and the July Movement’s guerilla struggle against the Batista regime in Cuba or the American revolution against British rule are examples. There have also been just rebellions, both peaceful and armed—Czechoslovakia and Hungary during the Cold War years—that failed. Revolution, of course, is a high-risk endeavor, and there are no guarantees.

Drif Debates BHL

In a public debate (in French) with Drif in 2012, the writer Bernard-Henri Lévy (BHL), an Algerian-born Frenchman, emphasizes the Algerian war of liberation against the French administration was heroic in many ways, and legitimate in so far as it attacked French military targets, but he remained adamant the Milk-Bar bombing was unjust, and an act of terrorism (the debate is also notable for the emotion and tension in the room. You can see, even 50 years after Algerian independence, terrorism, war, and colonization are still raw issues for both countries).

I believe that Zohra Drif was a terrorist, despite her status in Algeria today as a heroine of the revolution. She served time in a French-run prison in Algeria, so there has been a small measure of justice in her particular case. Yet she remains unrepentant, locked in the ossified ideologies of a 1950s revolutionary, the sad case of an aging militant still hostage to her youth.

Justice was not done, however, in the many cases of torture and deliberate killing of civilians by the French military, and this is a stain on France and its national reputation.

*

It is dispiriting that sixty years after the Algerian War, violence against civilians is still condoned because of historical injustices or unresolved conflicts.

It is both rational and logical to believe that the Israeli government has a right to protect its citizens, police its borders, and exact justice on Hamas. Palestinians also deserve a normal, sovereign state where they can enjoy the same rights of travel, work, prosperity, etc., as Egyptians, Jordanians, or Israelis for that matter. Palestinian civilians should not be killed or suffer collective punishment because of Hamas terrorism (Hamas using Palestinian civilians as shields, of course, makes this more complex). And if, somehow, you don’t see yourself or your family in either suffering or killed Israeli or Palestinian civilians, you’re either a partisan or numb.

The PA Condemns Hamas

It would be naïve to think there is much common ground, particularly now, between Israelis and Palestinians. But you’d think that the horror at the Hamas massacre could be a starting point. After all, even the Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas condemned the Hamas raid. You see worldwide protests in support of the Palestinian cause that suggest the tragic deaths in Gaza are the same, if not worse, than those in Israel.

It’s hard to convey how infuriating this claim is to Israelis, and the Jewish diaspora in general. Each person’s humanity is of course equal. On a human level, a tragic death is a tragic death, there is no distinction, and the family’s grief is righteous. But when we are talking about a geo-political dispute between state actors and/or a terrorist organization, intention matters when someone dies on a battlefield or a crime scene. There are no equivalencies between Hamas’ actions on Oct. 7 and those of the IDF in Gaza (so far).

It is right and understandable why Palestinian supporters highlight the civilians dying in Gaza, but it puzzles me why these groups in Europe and North America (where they are free to critique Hamas) can’t simply reject the murderous antisemitism and terror of Hamas: “We Stand for Palestinian Freedom & Condemn Hamas,” is a simple enough message.

*

One of the central cultural figures in the Algerian War was the Nobel Prize winning writer and pied noir Albert Camus. The war presented grave moral and intellectual challenges for him: he was a pied noir, a French celebrity, but also a member of the Parisian intellectual class, which included writers Jean-Paul Satre and Simone de Beauvoir, both of whom supported the F.L.N., seeing them as part of a wider Marxist liberation movement against western colonizers.

Camus genuinely wanted a peaceful resolution of the conflict between Arabs and pied noirs. Camus scholar Robert Zaretsky in VQR wrote that “unlike most pied noirs, Camus held that the credo of French republicanism applied no less to the colonized as the colonizers in Algeria.” In 1955 Camus “feverishly built the case for civilian truce in a series of editorials in the liberal French journal L’Express.” He believed that the opponents in the conflict should sit across from one another “to see and hear their fellow human beings.”

As a native of Algeria, Camus grasped the grim fantasy of both sides in the conflict. It is one that is likely familiar to some Israelis and Palestinians. Camus wrote “the French fact cannot be eliminated in Algeria, and the dream of a sudden disappearance of France is childish.” He also chided the French Algerian desire to “cancel out, silence, and subjugate” nine million Muslims.

The Cost of Independence

The F.L.N., in the end, did succeed in forcibly removing the French from their shores, but at a horrible price. It’s estimated that between 400,000 and 1.5 million Algerians died during the war. And this horror of violence and terrorism stirred up domestic disputes that surfaced in the 1990s in an Algerian civil war that claimed another 150,000 lives.

One can only imagine what may have emerged if Europeans and Arabs had found a way to live together in a multi-cultural state—independent from France—similar to that of Lebanon before the 1975 civil war or in the city of Alexandria, Egypt, which had a cosmopolitan mix of European and Arab residents until the rise of Islamic nationalism in the early 1960s, forced Europeans to flee the country.

In the end, Camus would alienate nearly everyone with his independent stance on Algeria. His fellow pied noirs scorned his liberalism and his fellow intellectuals, and the liberal establishment in France, broke with him after he rejected F.L.N. terrorism:

“I have always condemned terror. But I must also condemn terrorism that strikes blindy, for example in the streets of Algiers, and which might strike my mother and family. I believe in justice, but I’ll defend my mother before justice.”

Good, basic common sense is needed now more than ever. There is almost nothing the two “sides” can agree on, but let’s agree that men or women who leave bombs in ice cream shops or enter civilians’ homes with rifles and murder them are enemies of civilization, not soldiers or heroes. Let’s agree on this, and see where this narrow pathway of agreement can lead us.

Robert Fay has written for The Atlantic, The Los Angeles Review of Books and The Chicago Quarterly review.

![[Portrait of Leonard Bernstein in his apartment, New York, N.Y., between 1946 and 1948] (LOC)](https://robertfay.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/portrait_of_leonard_bernstein_in_his_apartment_new_york_ny_between_1946_and_1948_loc.jpg)