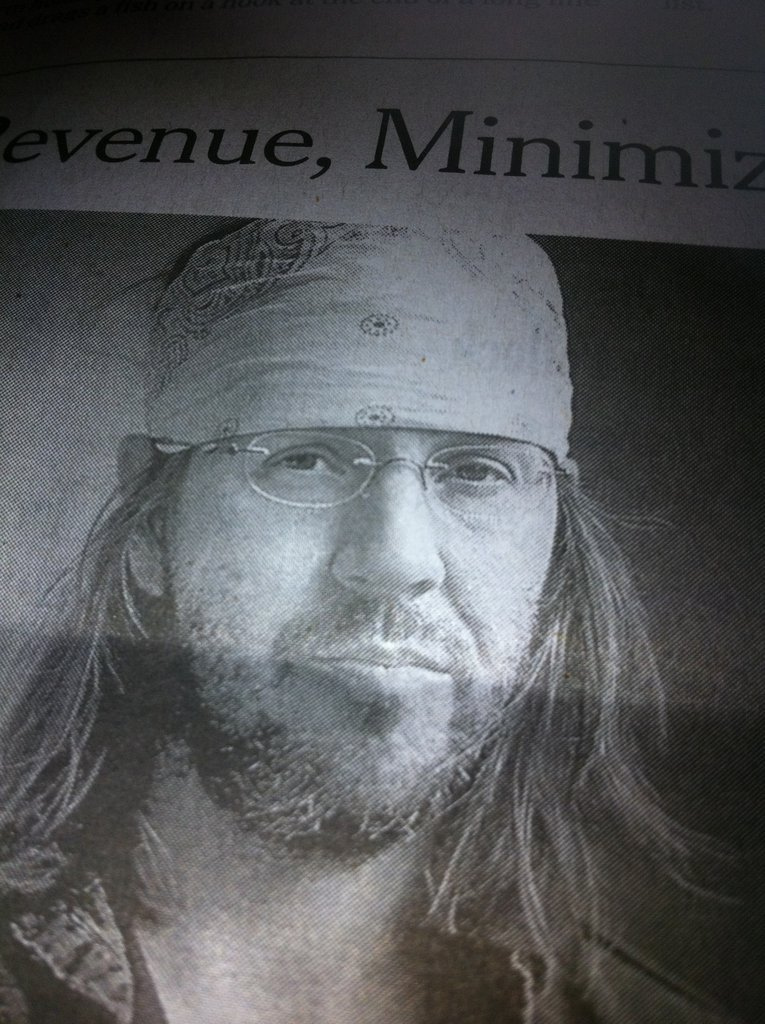

There have recently been a spat of blog posts and articles about the late novelist David Foster Wallace’s faith and whether the upcoming D.T. Max bio of Wallace will shed any light on this important subject. The latest round of interest in Wallace’s Christian faith (we don’t know exactly what denomination he identified with) was set off by a blog post by Daniel Silliman.

Silliman’s post was eventually picked up by The Daily Beast columnist Andrew Sullivan who has a fine article on the subject with links to a number of articles that provide us more clues about Wallace’s Christian faith and how it relates to his work. (Last fall Sullivan also wrote about an article I penned on Catholic writers wherein I referenced DFW’s interest in the Catholic Church).

I believe the significance of Wallace’s faith has been largely ignored because the practice of religion, and Christianity in particular, play almost no part in the lives of many literary editors, critics and writers. I think Sullivan gets it right when he writes:

My suspicion is that among DFW’s literary and academic peers, his church-going and attachment to Christianity (however complicated and complex) is not a feature of his life that intuitively is understood – and so the language and themes in his writing that point to this, whether overtly theological or not, tend to get downplayed.

Sullivan has a link to a video titled “A Life through the Archive” which is a panel discussion on David Foster Wallace‘s life and includes biographer D.T. Max. You can also read an excerpt from the forthcoming Wallace bio here.

Last December I blogged about David Foster Wallace‘s concern that writers today are ducking “the deep questions” of life a la Dostoevsky (also a believing Christian). Wallace complained about contemporary literature’s “thematic poverty,” but he just as easily could have criticized its spiritual poverty as well.

UPDATE: 12/8/2012 – I finished reading D.T. Max’s biography of David Foster Wallace, Every Love Story is a Ghost Story, and there was nothing in the book to indicate that DFW was a Christian or a Church-going person of any kind. Max writes that Wallace was interested in the Catholic Church for a time, but was ultimately not able to get past dogma, established beliefs, etc.

One item that may explain why people believe Wallace was a Christian, was his habit of referring to his AA meetings as “church” (Wallace was an alcoholic who regularly attended Alcoholic Anonymous meetings), which was apparently his way of concealing from journalists and others his struggles with addiction.

When Wallace was dating the writer Mary Karr (who later converted to Catholicism), he often talked about faith with her. Max writes:

“Wallace said he was trying to pray, because, even though he did not necessarily believe in God, it seemed like a good thing to do…So for a time Wallace too hoped to receive the sacraments, thinking that if he and Karr were to marry they could have a religious wedding (ultimately the priest told him he had too many questions to be a believer, and he let the issue drop). Wallace’s real religion was always language anyway.”