In André Aciman’s 1994 memoir Out of Egypt, he recounts the first meeting of his two grandmothers in an Alexandria, Egypt fish market. They two women discover they are both of Italian ancestry, by way of Ottoman Turkey, and as they talk further, “it suddenly occurred to them that of the six or seven languages they each spoke fluently, neither knew the name for mullet except in Ladino.”

This minor anecdote illustrates the extraordinary cosmopolitanism of Alexandria in the mid-20th Century. Aciman’s family was Jewish and had been in Egypt since the early 1900s, where they spoke French, which was the lingua franca of the upper-strata European community, who formed the commercial and trading backbone of the city, and were of British, Italian, Armenian, Greek, French or Jewish extraction.

When the U.N. recognized the state of Israel in 1948, there were approximately 80,000 Jews living in Egypt, primarily in Cairo and Alexandria. Jews in Egypt were part of a continuous community that went back over 2,000 years, predating the advent of Islam by seven centuries. This was also true for a number of Arab-majority countries prior to 1948. At the end of World War II, 130,000 Jews lived in Iraq, some of whom were descended from the Babylonian exile.

Today it seems nearly inconceivable that large Jewish communities could exist and thrive in Arab countries. It wasn’t until the mid-to-late 20th Century that a complex set of events: the rise of Zionism, the Holocaust, Israel’s creation, Arab nationalism, the Six-Day War, Islamic terrorism, the 1979 Iranian revolution, and so on, led us to our current moment.

Historian Avi Shlaim in his new book Three Lives: Memoir of an Arab-Jew, reminds readers that, not so recently, this rigid segregation of Jews and Arabs was not an insoluble fact. “There was a cosmopolitanism and coexistence that some Jews, like my family, enjoyed in Arab countries before 1948” and that these examples offer “a glimmer of hope.”

*

Coexistence is undoubtedly a rather low bar for human affairs. It does not imply equality between communities, cooperation, and certainly not harmony. But as an alternative to war and inter-communal violence, it is an enviable state-of-affairs, one where people can focus on what matters: getting married, going to school, starting families, pursuing careers, and so on.

For over six centuries (circa 1400 to 1918), the Ottoman Empire ruled over a pluralistic, multi-confessional empire, much of which consisted of Arab lands. Islam was the official religion of the state and Muslims were privileged within it, but Jews and Christians could practice their faith and manage their affairs with some measure of certainty and security.

“The Ottoman approach was wholly pragmatic,” writes historian Andrew Wheatcroft. “Jews and Christians were allowed free practice or their faith, but were required to pay a special tax for their privilege.” This does not imply, however, there were no persecutions. Wheatcroft documents how Jews were sometimes killed when they refused to pay the Janissary soldiers (the Ottoman Pretorian Guard) for “protection,” but these were not systematic or state-sponsored persecutions.

In 1844 the British Consul in Constantinople (now Istanbul) noted that the Muslim population was decreasing, while the “Christian and Jewish populations tend to increase in rapid ratio.” By 1878, the European population in the city had grown to more than 120,000.

It’s worth stating the obvious: the Ottoman Empire was neither a democracy, nor a free society in any sense of the word. It was a Turkish-centric empire with no elections, no independent judiciary, and the state of affairs for women, in particular, was horrendous. There should be no nostalgia for this colonial operation, but the mere fact that in 1900 there were approximately 390,000 Jews in the Ottoman Empire, speaks to a reality that today’s intractability is not the final word in Jewish-Arab relations.

Shlaim writes that the history of Jews in Iraq, for example, was one of largely successful integration and prosperity, “Iraq’s Jews didn’t live in ghettoes nor did they experience the violent repression, persecution, and genocide that marred European history.” Shlaim adds that “of all the Jewish communities in the Ottoman Empire, the one in Mesopotamia (present day Baghdad region), was the most integrated into local society, the most Arabised in the culture and the most prosperous.”

*

For the sake of clarity, I should declare that I’m a Zionist and I believe the creation of the state of Israel was right and just, and a logical response, not just to the Holocaust, but centuries of pogroms and antisemitism, from Portugal to Russia. The Zionist project to defend Jewish people, revive the Hebrew language, and forge a national identity from Jews across the diaspora, remains an extraordinary achievement.

I’m also certain that democratic, open societies are our sole bulwark against tyranny and oppression. For this additional reason, Israel remains a critical nation state in a region where strong men and military regimes predominate. But you’d have to be blind or foolish not to understand why the creation of the State of Israel was a disaster for the Arab population, in what was formerly Palestine.

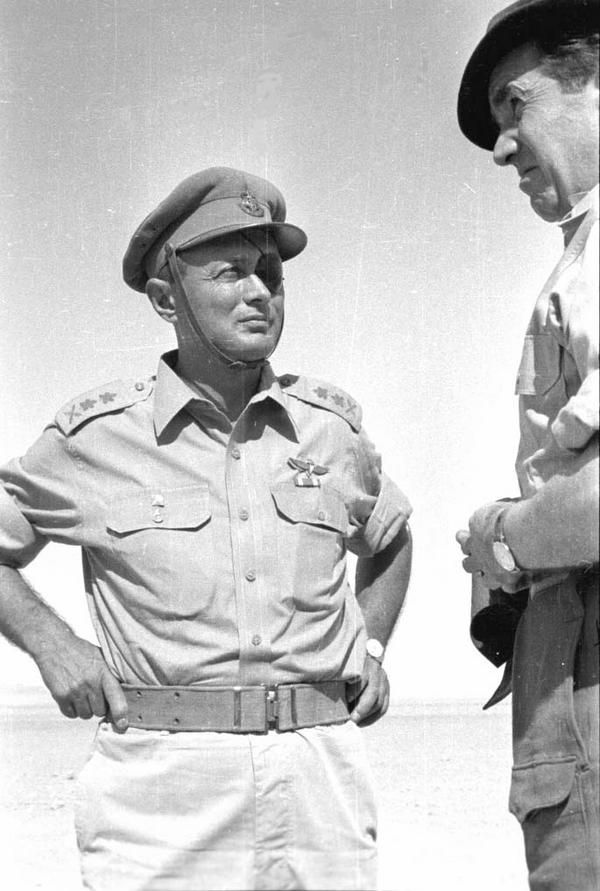

One thinks of Moshe Dayan’s famous 1956 eulogy for an Israeli murdered by Palestinians, where he acknowledges the source of Arab hatred and why Israelis will need to continually fight. “For eight years they have been sitting in the refugee camps in Gaza, and before their eyes we have been transforming the lands and the villages, where they and their fathers dwelt, into our estate . . . we are a generation that settles the land and without the steel helmet and the canon’s maw, we will not be able to plant a tree and build a home.”

The creation of Israel led, not only to the immediate 1948 War of Independence, and subsequent displacement of Arabs in what is now Israel proper, but to the humiliation of leaders in Egypt, Iraq, Syria, and Jordan as a result of losing the war. To deflect from this failure, Arab governments fomented domestic hatred against their Jewish citizens.

“A powerful popular wave of hostility towards both Israel and the Jews living in their midst swept through the Arab world in the wake of the loss of Palestine, and Iraq was no exception,” writes Shlaim. The Iraqi government passed a law in 1948 making Zionism illegal in the country, and Jewish people were subsequently dismissed from government and private sector jobs.

During the years 1950-51 over 110,00 Jew emigrated to Israel from Iraq, including Shlaim’s family, as life become more difficult for them. Similar factors in Egypt led to an exodus of Jews and other Europeans, though in Egypt’s case, it was more directly linked to the 1956 Suez War and Gamal Abdel Nasser’s Arab nationalism.

Aciman’s family held on for as long as they could. His father owned a successful factory, but one night in 1964, his father received a phone call. He put down the phone, looked at his family and said, “It’s started.”

Aciman writes how this was the beginning of calls “at all hours of the night . . . threatening, obscene, abusive calls . . . reminded us we were nothing, that we had no rights, and would be soon driven out, like the French and British before us.” His family left Egypt soon after.

*

“Jewish life in North Africa and the Middle East may not have been perfect, but Jewish people thrived for generations and made countless contributions to their societies in these Muslim-majority regions,” writes U.S. Foreign Service official Jairo Tutillo Maldonado. “This is a history that, if rehabilitated by governments of the region, could potentially rekindle friendships and even a renaissance of historic coexistence.”

A multi-ethnic, cosmopolitan Middle East is a possible path out of radicalism and antagonism toward the other. We see today that cities such as Algiers, Alexandria, Baghdad, Amman, are largely homogenous societies, inward-looking and parochial. Without Jewish or Christian residents, without peoples from across the Mediterranean, they have become cities bereft of the kind of dynamism that comes from the meeting of cultures.

The same can be said for parts of Israel, whether in the West Bank or East Jerusalem, where some Arabs have been removed, chased off, or even worse. The Arabic character and history of these places is indisputable, and these regions require vital Arab communities to retain their wholeness.

Aciman writes poignantly of the Jewish residents leaving Egypt in the 1950s and ‘60s. “On them . . . loomed the stigma—even the shame—of the fallen, the ousted, and it came with a strange odor that infallibly gave them away: leather.” He described how every family, knowing they’d eventually have to leave Egypt, usually had “thirty to forty leather suitcases, in which mothers and sisters kept packing their family’s belongs at a slow, meticulous pace, always hoping things might right themselves in the end.”

Aciman’s domestic reference to suitcases made me think—rather inexplicably—of the “coffee spoons” in T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” It’s a rather unsettling poem, a bit of stark modernist verse, where alienation and death are impossible to ignore despite the rather cozy, domestic details: “coffee spoons,” “taking of toast and a tea,” “I grow old . . . I grow old . . . I shall wear the bottoms of my trousers rolled,” and so on.

It’s been many years since I’ve read the poem and as I re-read the section referencing coffee spoons, I discovered that—as can happen with great poems—it seems to be addressing contemporary events, reflecting and refracting light in an entirely new way.

I can’t help but picture two people, old men perhaps, a Palestinian man in East Jerusalem and his Jewish counterpart in Haifa. They are both standing in their respective kitchens, after yet another difficult sleep. They don’t know one another, and will never meet or become friends . . . for this is impossible. They are world-weary, taciturn, wishing nothing but an end to trouble, but no longer knowing what to do . . . or even what to say:

“For I have known them all already, known them all—

Have known the evenings, mornings, afternoons,

I have measured out my life with coffee spoons;

I know the voices dying with a dying fall

Beneath the music from a farther room.

So how should I presume?”

Robert Fay has written for The Atlantic, The Los Angeles Review of Books and The Chicago Quarterly review.