Marcel Proust is forever being lost to myth, reduced either to a gossip who chronicled Parisian salons, or even worse, a withdrawn asthmatic overly sentimental for the past. This reduction makes no room for Proust’s admiration for technology or the diplomats and military men who made statecraft and war. Proust adored automobiles and was fascinated by German military aviation, and we find in Proust’s novels countless examples of his passion for military strategy, diplomacy and foreign affairs, which is personified in his character, the diplomat, Monsieur de Norpois.

Proust attended Sciences-Po, which had been founded to educate an elite for France’s civil and diplomatic posts. And though he developed a rich interest in relations between states, in the end, he knew a life of letters was his destiny. Proust biographer Jean-Yves Tadié writes, “The former pupil of the diplomatic section of the Sciences-Po never wanted to be a diplomat; yet he wrote the novel about diplomacy that those novelists who were diplomats—Chateaubriand, Stendhal, Gobineau, Giradoux and Morand—never wrote.”

*

The writer-diplomat tradition, though largely ignored in the history of letters, has been critical to the development of many European and Latin American writers. Eight poets with diplomatic experience, including Octavio Paz and Czeslaw Milosz, have won the Nobel Prize for Literature. Tadié references France’s great tradition, which reached its apex in 1937 when 50 percent of the diplomats from the Quai d’Orsay (The French Foreign Ministry) were published authors.

Mexico, among Latin American countries, has the most prestigious tradition with Carolos Fuentes, Paz and Sergio Pitol, a collection of writers so mighty, that one might assume there was a magical current uniting the diplomatic craft and literature.

Geoffrey Chaucer was one of the first literary men to practice these dual arts. He worked for the English Royal Service and conducted diplomatic missions on behalf of King Edward III in France, Spain and Italy in the 1360s. Yet I’m tempted to go back even further, to Paul the Apostle, the emissary of the nascent Christian nation—a proto Vatican diplomat if you will—who traveled through present-day Turkey, Syria, Greece and Italy. He recounted his adventures in his famous letters, his epistles, to the young Christian communities.

In his Letter to the Ephesians Paul makes a reference to his vocation, “Pray also for me, that whenever I speak, words may be given me so that I will fearlessly make known the mystery of the gospel, for which I am an ambassador in chains.”

Yet despite this rich history, little has been written on the subject. In biographical treatments, one-night stands and obscure book reviews often get more attention. Pablo Neruda’s biographer Adam Feinstein makes little mention of Neruda’s diplomatic work as a consul in Buenos Aires, among many other places, instead noting, “The eight months Neruda spent in Buenos Aires were ones of intense sexual activity—but not with his wife.”

In the case of Paz, the Nobel committee rightly acknowledged that his time spent in the diplomatic service was essential to his creative output, as well as providing him with leverage to influence—in this case by resigning—the actions of his own government:

“In 1962, Paz was appointed Mexican ambassador to India: an important moment in both the poet’s life and work, as witnessed in various books written during his stay there, especially, The Grammarian Monkey and East Slope. In 1968, however, he resigned from the diplomatic service in protest against the government’s bloodstained suppression of the student demonstrations in Tlatelolco during the Olympic Games in Mexico.”

Part of this neglect can be explained by the informal nature of these positions, particularly before the second world war. William Sommers notes that in 1870 “The Nation magazine complained that the U.S. Minster to Russia ‘spent nearly the whole term in a vain endeavor to be sober enough to be presented to the Emperor.’”

Writers often fill consular positions abroad, where they may advise on cultural matters, and—if they are lucky—avoid the weighty responsibilities thrust on formal ambassadors. Neruda spent years abroad working for the Chilean Foreign Ministry, but his entry into the service was due to informal networking.

In 1927 Neruda “bumped into a friend of the Foreign Minister’s, Manuel Bianchi,” writes Feinstein. “As soon as he heard of Pablo’s wish to go abroad, Bianchi arranged a meeting with the Minister, who handed the poet a list of vacant positions overseas. ‘Choose one,’ he said.” Neruda chose Rangoon.

*

India continues to maintain this venerable tradition, with poet Abhay Kumar serving in recent years as the Indian ambassador to Madagascar and Comoros. Kumar writes, “there are certain commonalities between the role of a poet and diplomat. A poet prepares the philosophical background or vision of a world—a philosophical framework of how in future things could shape up. A diplomat implements that vision.”

Linguist Dr. Biljana Scott believes the parallels are: curiosity and openness of mind and heart, a sympathetic and creative imagination, skill at matters of redress, and the appreciation that language matters. She emphasizes how skillful handling of ambiguity in language is critical: “In the arts, ambiguity is intended to allow for multiple meanings and multiple interpretations. Constructive ambiguity in diplomacy takes the form of adding a word that is positively connoted to a term that might carry negative overtones, such as: just war, smart and soft power, and enlightened self-interest.”

Ambassador Stefano Baldi, who is a career Italian diplomat, believes that “constructive ambiguity” creates the necessary time and space to change attitudes and reach consensus.

Kumar also thinks the isolation while serving abroad is important; the solitude from one’s homeland and friends is critical to providing writers the distance they need to dive deep, and create meaningful works. And for those who can’t be creative, the ordinary ones, they often succumb to booze.

*

The United States remains a curious outlier to this tradition, though with two prominent exceptions, Washington Irving and James Russel Lowell. Both men served as foreign ministers in the 19th Century and both were immensely qualified for the task. I must admit it’s difficult to imagine the author of “Rip Van Winkle” and “Sleepy Hollow” drinking his Spanish vermouth in Madrid or attending a bullfight, but he was a cosmopolitan character, and a wise choice to be Minister to Spain in 1842.

At 59, he was an internationally famous writer fluent in the Spanish language as well as a scholar of Spanish history. In 1828, the Spanish government had invited him and other scholars to explore documents covering the Spanish conquest of the Americas. The result was Irving’s book Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus.

When he arrived in Madrid, Irving’s household goods were held by Spanish customs. Irving was serious about his duties, yet equally earnest about his daily comforts. He wrote angry letters to custom officials, itemizing his belongings, which included: “three barrels of brandy, twelve hundred bottles of wine, one hundred bottles of liqueurs, six dozen packs of playing cards and five thousand cigars.” Daily necessities indeed.

James Russel Lowell was a poet, scholar and editor of the Atlantic Monthly, and greatly distinguished in his day, though entirely forgotten in our own. He served as minister to Spain from 1877 to 1880 and then minister to Great Britain from 1880 to 1885. Though Lowell was fluent in Spanish, it was the mastery of literary texts and historical documents—he was largely unable to manage everyday conversations. Yet he was a determined man, diligent in his duties and dedicated to learning colloquial Spanish. He described his daily schedule:

“Up at 8; from 9 sometimes till 11 my Spanish professor; at 11 breakfast; at 12 the legation; at 3 home again and a cup of chocolate, then read the paper and write Spanish till a quarter to 7; at 7 dinner, and at 8 a drive in an open carriage in the Prado till 10; to bed at 12 to 1. In cooler weather we drive in the afternoon. I am very well—cheerful and no gout.”

*

Proust never became a diplomat, of course, but he models how a sane, human-centered attitude can reframe conflicts between states. During World War I, he despised French chauvinism toward Germany, particularly among French intellectuals and the press. He was critical of composer Saint-Saëns who penned an article denouncing the music of German composers Wagner and Richard Strauss (a fashionable Parisian habit at the time).

He rejected the commonplace slurring of Germans and German culture, writing, “It is true ‘Boche’ does not figure in my vocabulary and things do not seem as clear-cut as they do to some people,” and adding in another letter. “If, instead of fighting a war with Germany, we were fighting one against Russia, what would they have said about Tolstoy and Dostoevsky?”

This is what only a writer could ask, even during the most horrible of circumstances. And today, the Russians can hack elections, assassinate soldiers, blackmail a president (perhaps)—and we must protest—but we must always reaffirm our allegiance, our citizenship to the Russia of Dostoevsky, Babel, Shostakovich, Bulgakov and Baryshnikov.

Like Paul the apostle, the first writer-diplomat, we must declare ourselves “ambassadors in chains” to what makes us human, what makes life worth living, for we are in perilous waters now, back in the same universe Bertolt Brecht described in the 1940s:

Empires collapse.

Gang leaders are strutting about like statesmen. The peoples

Can no longer be seen under all those armaments.

###

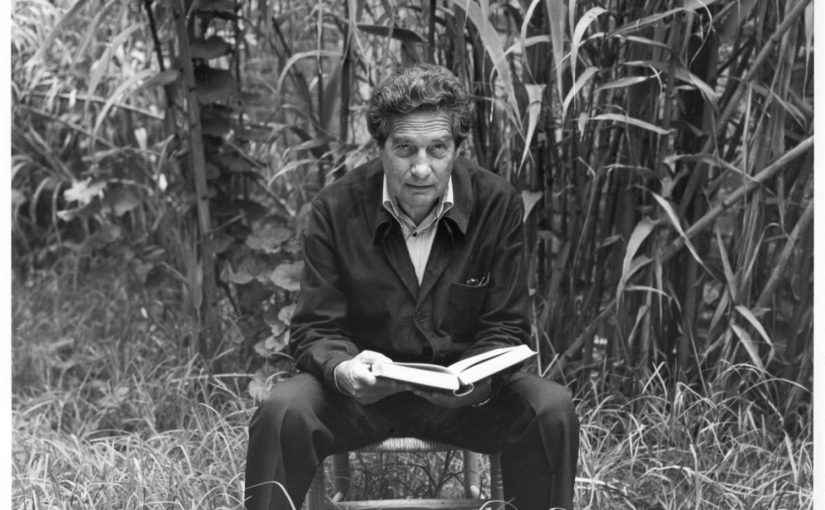

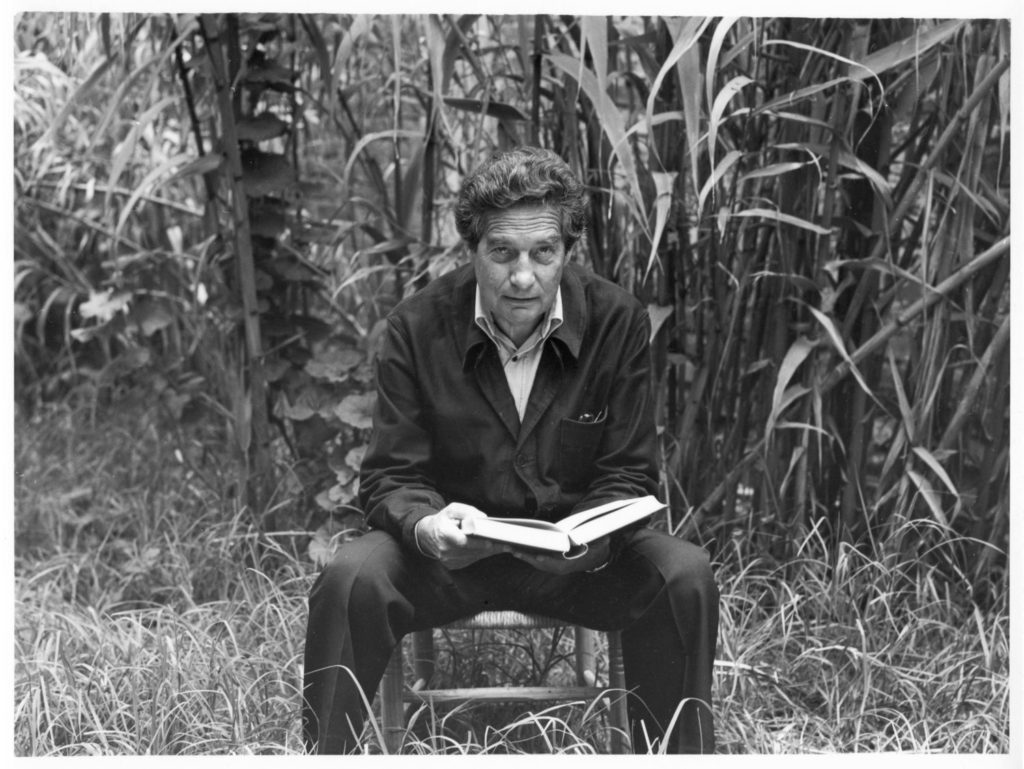

Robert Fay has written for The Atlantic, The Los Angeles Review of Books and The Chicago Quarterly review.