Grappling with James Joyce at the beginning of the 21st Century is similar to reading Shakespeare’s tragedies or even working your way through the Old Testament—you recognize immediately you are knee-deep in cultural source material. It feels less accurate to call Joyce a modernist than to say he was modernism, for it’s clear how much of our contemporary sensibility can be traced back to this peculiar Irishman.

I recently dug into the 1959 Richard Ellmann biography James Joyce. It needs little introduction: many people consider it the greatest literary biography of the 20th Century. I recently came across a David Foster Wallace essay on Joseph Frank’s Dostoevsky biography where Wallace alludes to Ellmann’s great achievement.

And though I’m still reading about the young, unknown Joyce at this point, the book is still thick with memorable anecdotes.

In 1902 a young Joyce met the grand poet of Irish letters, W.B. Yeats, who was then 37 years old. Joyce was cocky during the meeting and reportedly talked back to Yeats, which both impressed and upset the poet. At one point Yeats mentioned the French novelist Honoré de Balzac:

“When Yeats imprudently mentioned the names of Balzac and of Swinburne, Joyce burst out laughing so that everyone in the café turned round to look at him. ‘Who reads Balzac today?’ he exclaimed.”

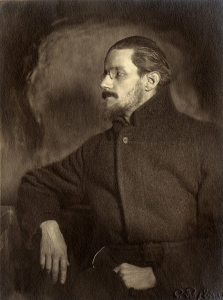

![]() photo credit: UggBoy♥UggGirl [ PHOTO // WORLD // TRAVEL ]

photo credit: UggBoy♥UggGirl [ PHOTO // WORLD // TRAVEL ]

Joyce, rather famously, was not a believing Roman Catholic from his adolescence onward, but he was (modestly) respectful of the Church’s traditions and a great admirer of the Jesuit order, whom he studied under as a boy. He once corrected a friend who labeled him a Catholic:

“You allude to me as a Catholic. Now for the sake of precision and to get the correct contour on me, you ought to allude to me as a Jesuit.”

There is also Joyce’s experience in Paris, where he was literally starving while failing to make ends meet with book reviews and English lessons. This is a letter from 1903 to his mother:

“Today I am twenty hours without food. But the spells of fasting are common with me now and when I get money I am so damnable hungry that I eat a fortune before you could say knife. I hope this new system of living won’t injure my digestion.”