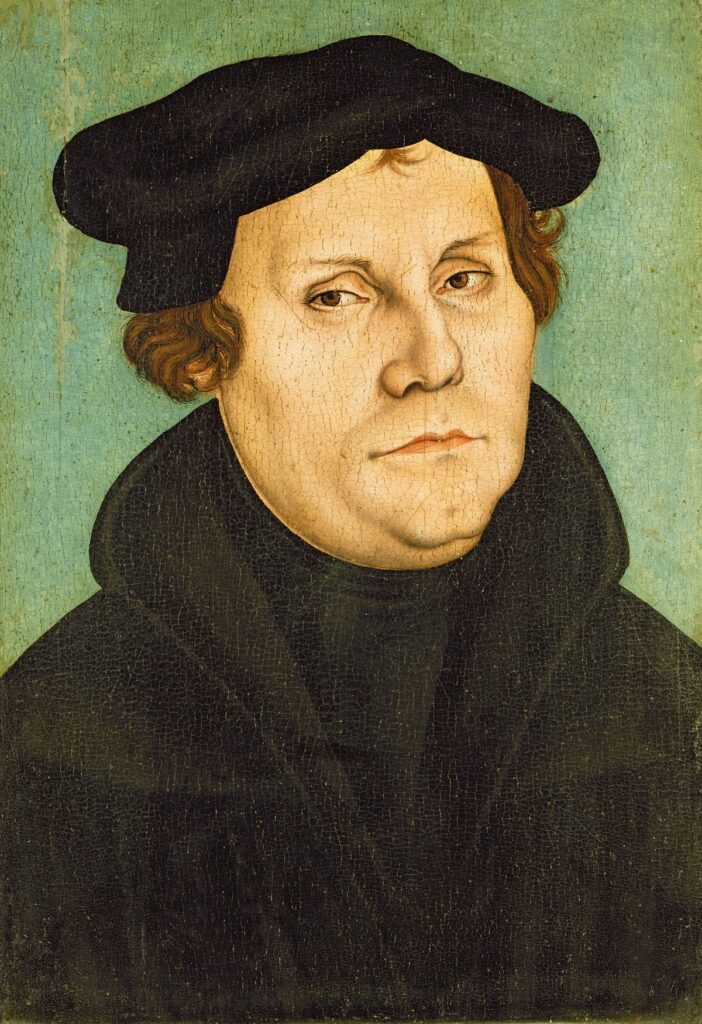

Martin Luther spent the winter of 1522 hiding at Germany’s Watburg Castle. It was a smart move, for he had challenged the Roman Catholic Church’s monopoly on biblical interpretation and the pardoning of sins, and was not likely to receive a Christmas card, or much else in terms of support, from Pope Adrian VI that year.

This rather anxious Augustinian monk wasn’t a conscious saboteur of institutions and norms, he was no Jacobin, but a devout personage, and almost certainly a sufferer of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder by today’s standards. His writings reveal a nagging fixation on whether he was in a state of mortal sin or not (no small matter in 16th Century Germany); in the Catholic tradition, this is a spiritual malaise known as “scrupulosity” and it often afflicts the super-devout, and has included a number of canonized saints throughout the centuries.

We also know that Luther, despite his non-serviam, was not an agent provocateur, because he was appalled at the subsequent damage and sacrilege committed against Catholic churches and monasteries in his name. A contemporary report catalogs the damage to the Reinhardtsbrunn monastery in Germany: “With sacrilegious hands, the rabid people smashed all twenty three altars, with their precious carvings, sculptures and holy images, because they were objects of Catholic veneration of saints . . . they emptied the holy oil of consecration from its beautiful jug and poured it on the ground.”

In the language of today’s politics, we can say Luther’s “Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences,” his so-called “95 Thesis,” had been weaponized, and it wasn’t long before this super-charged reform movement had come to the wilds of North America.

The late conservative historian Samuel P. Huntington believed American national identity was initially formed by Protestant Christianity, something he called “Anglo-Protestant culture.” Huntington designated the early New England settlers, the puritans, as the founders of this culture, and the puritans were nothing, if not strict Calvinists. Historian David Hall writes, “citizens on both sides of the Atlantic believed that the intellectual descendants of Calvin were the founders of colonial America.”

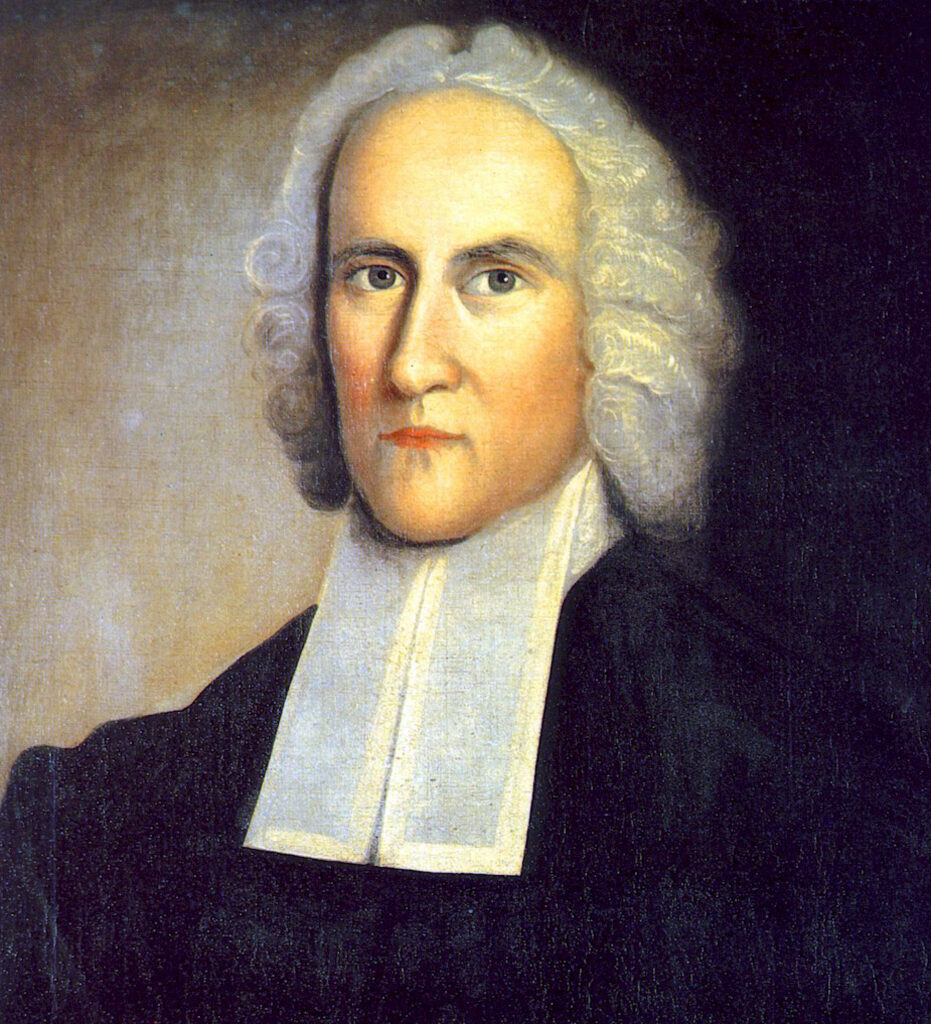

The Calvinists were undoubtedly descendants of Luther’s scrupulosity, but their reductionist version of Christian discipleship, wherein man was entirely polluted by sin, quickly diverged from Luther’s direct line; we can see this divergence in a superficial look at the Christian communities of two contemporaries: J.S. Bach and American theologian and preacher Jonathan Edwards.

The former was a choirmaster in a German Lutheran church whose liturgy and preaching, if observed today, would strike many as nearly indistinguishable from a Roman Catholic church; while Edwards, the Calvinist preacher in Northampton, Mass., served at simple wood-clad churches—though dignified by today’s brutalist standards—that are largely indistinguishable from whitewashed, New England town halls. And when it comes to doctrinal matters, he wasn’t just down on Catholics priests and indulgences, he actually decided human beings were all bad, all the time, and born with perdition as their loadstar, and it was only God’s sympathy for our wretchedness that saved us.

One simple way to appreciate how American Calvinism diverged from the Lutheran high-church experience is to listen to Bach’s Mass in B Minor and then read through Edwards’ “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God;” though, for sanity’s sake, perhaps this shouldn’t be done on the same day.

The weaponization of theology was not entirely perfected until a Swiss bible thumber named John Calvin turned German scrupulosity into a war on aesthetic sensibilities, preaching, “. . . the first vice, and as it were, the beginning of evil, was that when Christ ought to have been sought in his Word, sacraments, and spiritual graces, the world, after its custom, delighted in his garments, vests and swaddling clothes; and thus overlooking the principal matter, followed only its accessory.”

Scratch a Calvinist doctrine, and beneath the surface you will find a prudish fear of the sensual life; a horror of ornamentation, fashion—both ecclesiastical and secular—objets d’art, architectural refinement, grape and grain, in other words, some of those very things that make life pleasurable.

*

Today, in nearly any American town, you can easily find a church building that has all the sacred mystery of a wholesale auto-parts store or, if you’re lucky, the architectural distinction of a Motel 6. But this anti-aestheticism, this distrust of ornamentation isn’t confined to evangelical churches alone, it’s the trace minerals in our environment, the hammer and saw in our toolboxes. You can find it in Shaker furniture; the architecture of Frank Llyod Wright; the simplicity of the White House; the prose of Ernest Hemingway, Raymond Carver and Lydia Davis; the music of Philip Glass; the paintings of Mark Rothko; examples abound—and these are the best examples of this phenomenon, the examples of individual artists or communities who were not entirely overcome by this Genevan inheritance.

And, of course, U.S. history contains a number of distinct artistic movements and artists who entirely rejected puritan restraints; African-American Jazz artists are the preeminent example, but other examples include the paintings of Jackson Pollack and Jean-Michel Basquiat and the prose of Jack Kerouac, all of whom—not coincidentally—were sophisticated Jazz connoisseurs.

I suspect many American novelists today would consider themselves immune to their puritan forbears, because they are secular, or if religious, affiliate themselves with gay-friendly churches or attend Unitarian services; but many writers remain enmeshed in a Calvinist anti-aesthetic, plying their Iowan, wood-shop craft under the delusion of novelty; producing well-plotted, embellishment-free works with all the originality and linguistic panache of a pharmaceutical brochure.

These men and women are undoubtedly earnest, multi-degree bearing citizens with the skill to invent characters and zippy narratives that can both entertain and edify, helping to ensure the book club, hummus and pita crowd, who can, as a result, conclude their busy weeks with the sweet, self-satisfied pride of believing—just by reading a 300-page story about fictional people—that they are now sanctioned empathizers of marginalized peoples everywhere, from Calcutta to Camden, New Jersey.

*

Roberto Bolanos’ novel Woes of the True Policeman begins with a character, Oscar Amalfitno, who is familiar to readers of Bolanos’ masterwork 2666. Amalfatino describes a bizarre literary theory developed by his gay lover, Padilla, a hard-scrabble poet from the streets of Barcelona. “According to Padilla . . . all literature could be classified as heterosexual, homosexual or bisexual. Novels, in general, were heterosexual. Poetry, on the other hand, was completely homosexual.” Padilla then goes onto to divide the homosexual category of poets into a number of sub-categories, using various slang terms for gay men, queers, sissies, freaks, and so on, as well as number of additional epithets likely to offend the sensibilities of 2021 America.

Padilla’s theory is, of course, ridiculous. But it is great fun to read his endless digressions on specifically why Pablo Neruda is this type of homosexual poet in his system, while Walt Whiteman is quite another. Bolano has fun with language, stereotypes, the egos of the literati, while casually demonstrating an encyclopedic knowledge of Spanish and Latin American poets.

Novelist Alexander Theroux in a largely-forgotten 1972 essay titled: “Theroux’s Meta phrastes: An Essay on Literature” did not do anything as banal as classifying novelists, but in his acrid condemnation of linguistic skinflints, he did loosely employ the aesthetic and theological tensions between Catholicism and Protestantism to make his point. He wrote: “O let the long-nosed, umbrella carrying joykillers kick the pins out from under metaphor and simile, color and allusion. It was just exactly what that simpering Genevan woodcock, Jack Calvin, tried to do to the Roman Catholic Church, and I for one say poo.”

And Theroux, a former Trappist monk, who knew his Latin as well as he knew his Baltimore Catechism, remained baffled that American writers continued to maintain an “utter void apparently when it comes to a knowledge of what we have inherited from the beautiful Franco-Latin-English trilingualism of the Norman Period.”

Theroux is a man who sees villains everywhere—one likely reason he is persona non-grata in today’s publishing world—and he nominates Mark Twain as the grandfather of the American “less is more” set. “‘Eschew surplusage,’ snapped Twain, that anti-European, anti-Catholic pinchfist from the American Midwest . . . Rip off that wainscotting! Slubber that gloss! Steam down those thrills!”

There are occasions in American literature where this tension has generated its own creative energy, most spectacularly in the poetry of Robert Lowell. Lowell came from a distinguished family of New England bluebloods with deep Yankee, puritan roots, yet he briefly converted to Catholicism during a critical creative period in his twenties, and the cosmological outlook and aesthetic influence of the Catholic Church never left him. Kay Redfield Jameson, in her recent book on Lowell and his bi-polar disorder, writes how within Lowell “the battle raged between Calvinism—the New England Protestantism that he had known longest and breathed most deeply—and the Catholicism that has an adult he had taken to heart and mind. The clash entered into his work violently and unforgettably in the poems of Lord’s Weary Castle.”

The corrective to the codified, linguistic reductionism within American letters is, of course, that there is no real answer. There is no Union of North American Fiction Writers to issue a memo banning the use of realist/naturalistic/minimalist modes of fiction in American letters, but there are certainly grumblings of discontent. Prominent critic Dusting Illingworth recently wrote of his exhaustion with realistic fiction: “more and more I find the realist novel’s conscription of detail to describe and systematize the external world frictionless, even embarrassing.” And Steven Moore’s new book Alexander Thoreux: A Fan’s Notes, can only be read as a (subtle) plea by one of America’s most important critics to rethink and reabsorb the work of this singular author.

In the end, what seems to be missing is a simple enchantment with language, which brings me rather inexplicably to a most un-American writer, Rabelais, that 16th Century French, a rascally character who is a historical reminder that literature can be fun, raunchy, edifying, linguistically complex, and well, fun. Rabelais is one of Thoreaux’s heroes, and also quite conveniently for my argument, a creature of Catholic culture, albeit a rebellious one, who spent time in two religious orders as a novice, the Franciscan and the Dominicans, before becoming a secular priest, (i.e., not affiliated with a religious order), and did so without permission from the church, while also managing to have two children from an relationship with a lovely widow. Needless to say, he was no choir boy, but this is precisely the point.

The critic and scholar L. Cazamian, in his A History of French Literature, sums up the pure joy of reading Rabelais, which is really the whole point of this essay in fact: “ . . . words—an inexhaustible store of language, learned or popular, national, provincial, dialectical, foreign, with artificial terms thrown in; words, that are to the writer a source of unique joy.”

Audio Version: You can listen to an audio version of the essay on the Feeling Bookish Podcast.

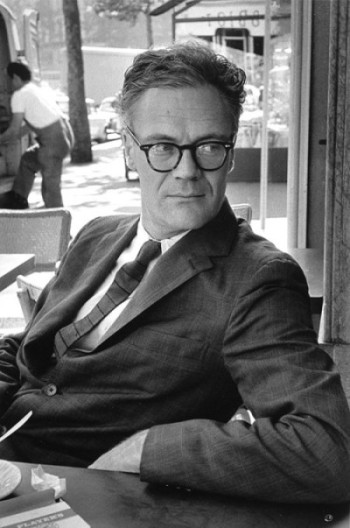

Robert Fay has written for The Atlantic, The Los Angeles Review of Books and The Chicago Quarterly review.