The line between truth and fiction is becoming more tenuous with the rise of “creative nonfiction” and the continued popularity of the memoir. The debate over where and how to draw the line intensified recently with the publication of the book The Lifespan of a Fact by the creative nonfiction evangelist John D’Agata with Jim Fingal. D’Agata has admitted to changing facts in the interest of the larger story and his personal artistic vision.

Lee Gutkind in an article on D’Agata’s book in the Los Angeles Review of Books writes: “And so it goes: a constant struggle between the writer’s obsession with style and the fact-checker’s passion for substance.”

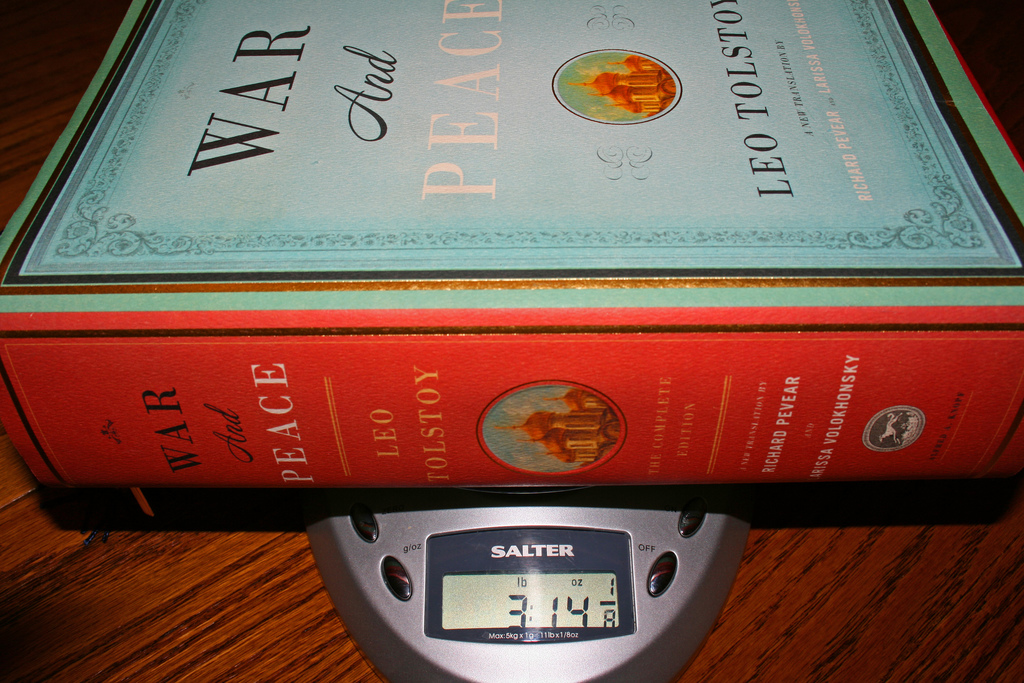

Lovers of fiction and the literary novel might be tempted to look back at the mid-20th Century and the 19th Century as golden periods when the novel was the supreme and unquestioned creative vehicle for the day’s most talented writers. Yet even Leo Tolstoy, who wrote arguably the most iconic novel of the period in War and Peace, was not comfortable defining his masterpiece strictly as a novel. The introduction to the much heralded translation of War and Peace by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky (2007) quotes an 1868 magazine article by Tolstoy where he explains his reluctance to categorize the book according to the conventional forms:

“It is not a novel, still less an epic poem, still less a historical chronicle. War and Peace is what the author wanted and was able to express, in the form in which it is expressed. Such a declaration of the author’s disregard of the conventional forms of artistic prose works might seem presumptuous, if it were premeditated and if it had no previous examples.”

Tolstoy goes onto to add that the history of Russian literature is filled with great books that were a departure from what he calls “the European forms.” And what was it that Tolstoy was hoping to achieve with his massive “departure” from the novel?

Critic and translator Boris de Schloezer argues his consistent aim was to tell the truth:

“All the forces of his imagination, his power of evocation and the expression, converge on that one single goal. Outside of any other religious or moral considerations, Tolstoy when he writes obeys one imperative, which is the foundation of what one might call his literary ethic. That imperative is not imposed on the artist by the moralist; it is the voice of the artists himself.”