I was late to the party when it came to reading Joan Didion. For years I had the vague sensation that Didion wasn’t for me. It was one of those unapologetic prejudices people have for certain writers, a prejudice that ended when I picked up a copy of The Year of Magical Thinking. It was evident from the start why Didion was held in such high regard—she was good. And yet, because I’d read Magical Thinking and its meditation on her husband’s death, I decided to pass on Blue Nights, her new memoir about the death of her 39-year-old daughter.

If it’s a truism that a critic should always review the book in hand, and not the book they wish had been written, then I’ve eagerly crossed the line. My own “magical thinking” involved—not denying the death of writer John Gregory Dunne, as Didion initially did—but wishing that his death and her subsequent grief wasn’t the focus of the book. I found myself skimming over passages about the Beth Isreal ICU or long meditations on grief to find those where Didion recalls her marriage and life in Los Angeles in the 1960s and ‘70s.

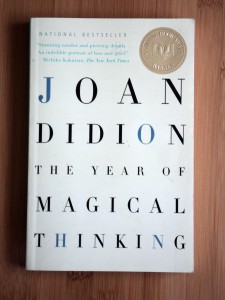

![]() photo credit: softestthing

photo credit: softestthing

I wanted to hear about two writers living a blessed life of work and play in a California that no longer existed. I wanted it to be LA in 1971 when Didion wore oversized Rachael Zoe-like sunglasses and chain-smoked cigarettes as if they were elixirs. I wanted to go back before all the dying:

“One summer when we were living in Brentwood Park we fell into a pattern of stopping work at four in the afternoon, and going out to the pool. (John) would stand in the water reading (he reread Sophie’s Choice several times that summer, trying to see how it worked) while I worked in the garden….Just before five on those summer afternoons we would swim and then go into the library wrapped in towels to watch Tenko, a BBC series, then in syndication, about a number of satisfyingly predictable English women…..At seven or seven thirty we would go out to dinner, many night’s at Morton’s. Morton’s felt right that summer. There were always shrimp quesadilla, chicken with black beans.”

You get the idea. There are similar passages capturing life in Malibu and stays in Hawaii. It’s the writer’s life as well as the life of a marriage, rendered simply by a great writer.

“…many night’s at Morton’s. Morton’s felt right that summer.” What a beautiful line. It’s worth reading an entire book just to hit upon such a line.

Yet the book is not a memoir of marriage, but a book about death and loss. And in her confrontation with grief, Didion soldiers under a strict scorched-earth policy, burning down any hint of solace or false comfort in her way.

“Only the survivors of a death are truly left alone,” Didion writes, “The connections that made up their life—both the deep connections and the apparently (until they are broken) insignificant connections—have all vanished.”

After reading Magical Thinking I can only assume Blue Nights will be even more punishing. A recent review by writer Rachel Cusk in The Guardian confirms this suspicion:

“Didion’s strategy, or rather her instinct – the instinctive response to chaos – is to repeat herself. She struggles to revive the form and style of her earlier book, to make it live again; she repeats anecdotes, and often sentences, word for word; she creates repeating prose patterns whose effect, in the end, is to confer the author’s own numbness on the reader.”